Sometimes we take health workers for granted, but Rehana Lothian is full of admiration for two international health workers’ efforts during the pandemic. Portraits by Donna Richmond.

Kim Codeth Stensmar is a qualified nurse from the Philippines and speaks five languages, having arrived in Sweden after studies and work in Finland. She is friendly, with a constant smile and pleasant manner. As we sit down to talk, it doesn’t take long before I realise how nice and reassuring it would be to have someone like her looking after you when you’re unwell.

RL – Where are your roots and how do they differ from where you live now?

KCS – I grew up in San Isidro in the Philippines, a small agricultural town far from the big cities. Mum was my big influence and role model. She cared for my grandmother and inspired me to become a nurse. I knew what I wanted to do from an early age, I never thought of doing anything else. My dream was to study in Finland, where my aunt lived, even though I didn’t really know where it was. The dream came true when I was 16 and enrolled at nursing college in Vasa, but adapting to life in Finland was quite a process. I had no idea about other cultures other than what I had watched on American TV so, yes, Finland was a big shock. The first things I noticed were the fresh air and that there were so few people. I also couldn’t understand why all the houses were red. At that age I was clueless and, sometimes, lost and scared. After a few years I wanted to go home but didn’t tell anyone because there was a lot of pressure on me to succeed – my family had done a lot to get me here. I kept at it and my aunt made me practice Finnish on my days off.

RL – How did you begin your career?

KCS – When I was studying at the nursing college in Vasa. I worked as a hospital cleaner for the first few months. I worked the night shift, then went to college the next day. Sometimes I worked for two days with only two hours of sleep. I qualified as an assistant nurse and worked as such while studying towards nurse level. The nurses made a great team, they were like my family. We had so much fun, but I have no idea where I got the energy from. Vasa is a relatively small town and I quickly made friends, found a church and felt part of the community – but, at the same time, I was thinking about home and going back to farming. I was still homesick.

RL – But instead you moved to Skellefteå. How did that happen?

KCS – Love. It’s a strange story but one night I was babysitting for friends. The kids were fast asleep and boredom set in. In short, I went online and eventually got in touch with a man in Sweden called Simon, who initially thought I was one of those internet robots. That’s how our relationship began. We are now married. So instead of going back to the Philippines, I set my sights on Skellefteå. Once here, I started work in a care home before moving on to hospital work as an assistant nurse, then nurse. Just like Vasa in Finland, it was rather quiet in northern Sweden but the Skellefteå Girl Gone International group was a great help for friendship and company.

RL – How did it feel to work in healthcare during the pandemic?

KCS – Stressful. Managers had to make decisions based on the number of staff off sick and the number of patients on the ward. I was exhausted leaving work but we didn’t complain. The stress was greatest on the managers making those decisions. We dealt with whatever cases came in on the day and just hoped there would be no emergencies. Teamwork was really good and at the end of each day we got together to say “Bra jobbat idag”. It’s so rewarding to see patients you have treated being well enough to go home.

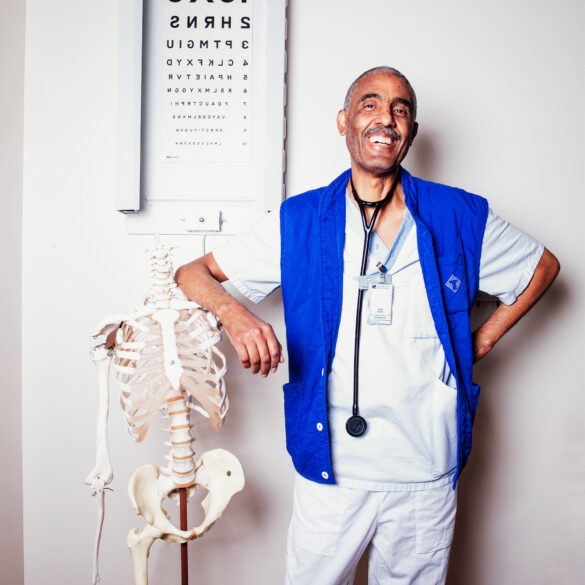

Ibrahim Kebire came to Skellefteå for a five-week posting as a doctor 12 years ago. He liked the city and its people so much that he is still here and firmly rooted. If you know him, you’ll know his friendly, almost childlike, smile, and be struck by the extraordinary amount of energy he has for his job as a general practitioner at Heimdalls Health Centre. And it really is a vocation, a part of his fabric. We’re sitting down in his office wearing masks but, above the mask, his bright eyes tell me healthcare remains one of his favourite subjects after more than 15 years working in Sweden.

RL – Where are your roots?

IK – I was born in Asmara, Eritrea, and moved to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, at the age of five. Later on, I studied medicine in Libya. Where I come from everyone dreams of being a policeman or a doctor; I chose the latter. My parents, siblings, the whole community actually, influenced my upbringing. It’s like everyone cheers you on to be a better person. It’s very special and this is one thing I miss from home – it’s like having a huge family, always someone around whether you like it or not.

RL – How did you begin your career?

IK – By studying hard. It really was a struggle, working late into the night and sitting tough exams. It felt

never-ending and my limits were really put to the test. The war in my country seemed endless, so I didn’t want to go back. It had lasted the whole of my lifetime but suddenly stopped not long after I arrived in Sweden as a refugee. The idea of going back surfaced but the war started again, so staying in Sweden it was. A job as a refugee counsellor gave me a stepping stone and a great insight into the Swedish system, the language, how the authorities work and so on. At that time most of the refugees were from the former Yugoslavia, Eritrea, Somalia and the Middle East. I had been to Europe a few times before, so arriving here wasn’t a shock – more like a long process of adapting to the Swedish way because people worked differently and family life was different. In the early days home was a hotel room shared with other refugees, who became not only friends but also like family. I was surrounded by people and suddenly felt alone when I got my first flat. Being able to practice as a doctor in Sweden required more exams because I had qualified outside of the EU. Once over that hurdle, my first job was in Gothenburg before specialising as a family physician in a town in Småland in southern Sweden.

RL -Why Skellefteå?

IK – Curiosity saw me travel around Sweden whenever I could, taking in the counties of Småland, Dalarna, Värmland and Västmanland, for example. But I was also fascinated by Norrland, asking myself what it would be like going somewhere so cold or where you could see the midnight sun? My job in Skellefteå was only supposed to be a short stint, covering for five weeks. But, as you can see, I stayed. Skellefteå is perfectly sized; you can walk and cycle to most places and the patients are so appreciative. People are respectful, open and friendly. I’m a natural traveller but I’m settled here. To any newcomer, I’d say: make the most of it, learn the language, get involved even if you don’t intend to stay. You never know. Just look at me. I came for five weeks and I’m still here after 12 years.

RL – How did it feel to work in healthcare during the pandemic?

IK – The whole world was unprepared. It got very intense, then people started dying even around us. The intense pace meant that we eventually became exhausted. We tried our best, but we got it [Covid] in our clinic. Fifty per cent of staff got it within a few days. I caught Covid myself and was out for three weeks. At first I wanted to work from home but had to stay in bed, unable to do anything. My colleagues were really great, delivering groceries to my door, sending messages and checking on me. As Covid struck, we tried our best and changed our routines, just like other healthcare settings all over the world. It wasn’t easy but, despite our depleted numbers and being so stretched, the clinic remained open throughout the pandemic. The disease is no longer at pandemic level but the risk remains. What happens if it flares up? Will there be another virus? Hopefully, whatever happens in the future, we’ll be more prepared. My hope is that we’ll be able to better tackle the heavy impact on mental health as well as physical health should something like this happen again.